Furrie Friends

Leelee Brazeal’s Furrie Friends does not whisper. It stares you down and then starts talking too fast, filling the air with questions you do not want to answer. The background is a restless black with pink bleeding through like raw skin. Figures emerge in chalky lines, part animal, part human, part mask. A cat-woman in a bikini. A rabbit in briefs who looks like he has been caught in the wrong room.

The surface is scattered with question marks and a list of possible answers to questions no one sane would ask. Are you a pedophile. A wife beater. A control freak. A sadist. The words line up like a police report written by someone who cannot stop laughing.

It is funny until it is not. That is the trick. The humor curdles into something darker. The text closes in. You realize it is not just about the ridiculousness of online dating. It is about the way we present ourselves when the truth is too hard to show.

Brazeal’s hand is raw and direct. Nothing is softened. The painting works like a dare. It holds you there, makes you read every word, and leaves you wondering which of your own answers would be yes.

My first last and only visit to jail

My First Last and Only Visit to Jail isn’t so much a painting as a public confession rendered in color, a mugshot of the soul. You can smell the stale air and the institutional beige, feel the slow drip of time under buzzing fluorescent lights. The work is part performance, part crime scene, part diary entry written in capital letters. There’s humor here because you lived to tell it, but the humor is dry, brittle, the kind that cuts its own tongue on the way out.

The figures (or maybe the ghosts) in this piece are caught in a weird suspended animation. They’re flat but vibrating, pinned like butterflies yet twitching under the glass. The brushwork is loose but knowing there’s no decorative fussing, just the raw shapes and colors of someone telling the truth without dressing it up.

This isn’t prison art, it’s post prison art. It’s art that understands the difference between doing time and serving it. You can almost feel the moment you walked out: the hard sunlight, the relief mixed with shame, the absurd urge to laugh. And by putting it here on canvas instead of in a Facebook post you made it immortal. You turned a moment you’d rather forget into something no one will be able to.

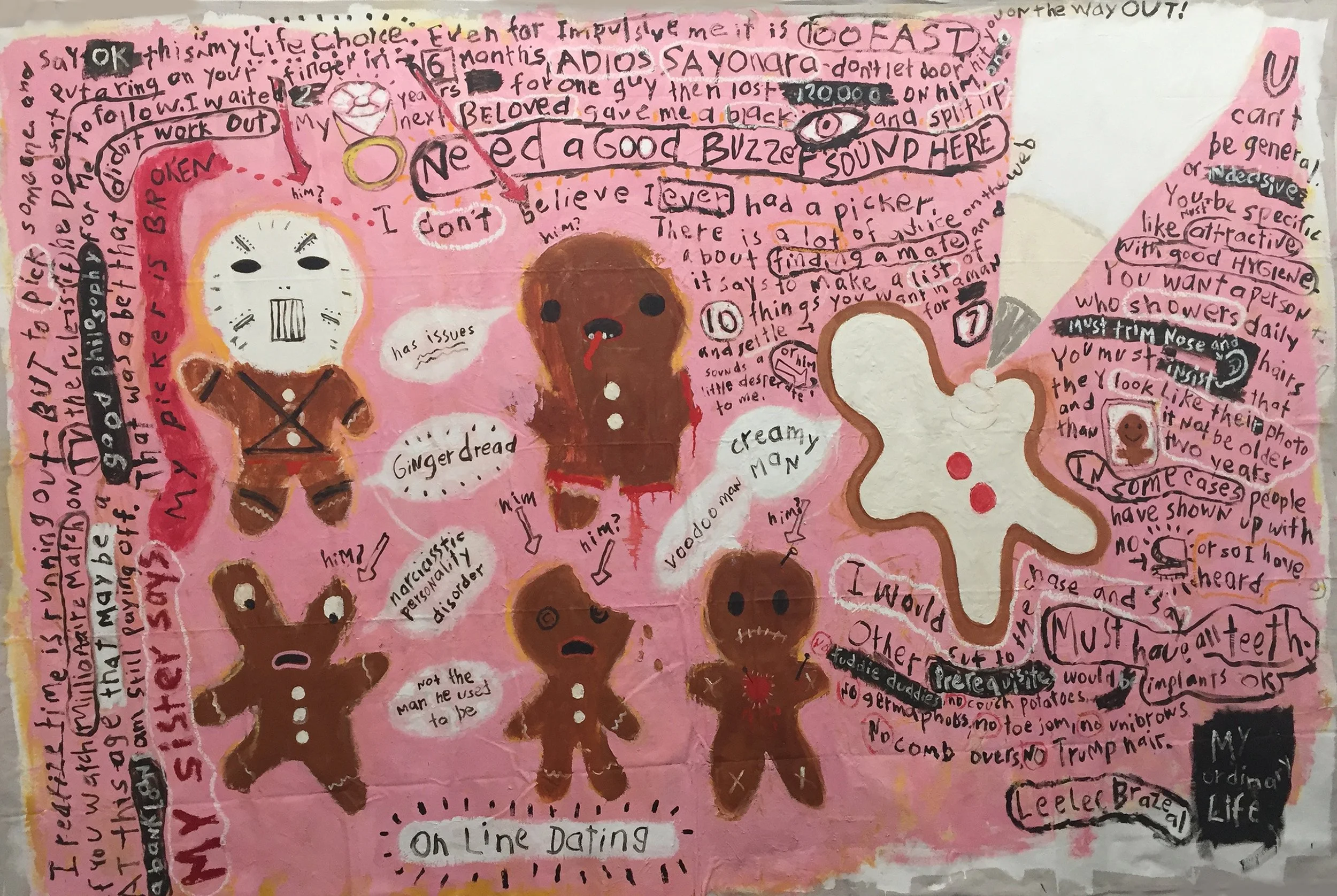

Gingerbread dates

Brazeal turns the whole ordeal into a visual rant. The questions are both ridiculous and depressingly familiar. Will you clean the toilet. Will you lose weight. Will you keep your promises. Will you wear crotchless panties. Will you be less of yourself so I can feel more like me. By repeating them across the surface, the painting gives them a grotesque permanence. They stop being requests and become the wallpaper of modern romance.

What makes the piece sing is its refusal to answer any of them. Instead, it lets the viewer stew in the noise, forcing you to decide if you are complicit, amused, or simply exhausted.

This is deadly serious.

Dating Advice-Gingerdread

The Black Dog Is Waiting

The black dog stands in the shelter run, calm but watchful, the one most visitors pass without a second glance. It’s not the color or the breed that keeps him waiting, it’s the quiet fact that black dogs are too often overlooked, as if their darkness makes them invisible. Children should learn long before they can drive or date what it means to care for another life-how to feed, walk, groom, and listen to an animal until it trusts you. Boys should be taught that neutering a dog is not a loss of pride but a gift of safety and health. To have a dog should be a mark of honor, a badge that says you are capable of patience, kindness, and responsibility. In a better world, the black dog would be chosen first, not last, and we would measure our worth how well we keep our promises to the ones who depend on us.

The Chorus of Yes and No

In On-Line Dating, Lee Lee Brazeal pulls the whole mess of intimacy, gender politics, and performance art into the same cramped bed. The painting is loud even before you read a single word. The bodies are stripped down to their underwear, but they are drowned in a sea of interrogation, a torrent of small humiliations and absurd requests. It’s a dating profile turned crime scene, a Q&A that feels like it never ends. The words snake through the composition like gossip at a bad dinner party. Some questions are banal, others cut to the bone. All of them ask for a piece of the subject without offering anything back.

The two central torsos act like blank avatars. They could be anyone, which makes them everyone. Around them, the words press in from all sides, an overgrowth of expectation, judgment, and low level threat. You can feel the claustrophobia. The black and white shapes are punctured by pink highlights that flash like neon signs in the dark , sexy, cheap, and slightly menacing. This is not just about dating. It is about the way women are asked to audition for the role of “acceptable partner” every day, as if love were a job interview with no HR department.

Oh my god. YES. Finally a painting that actually feels like the internet, that feral, godless landscape where hope and delusion swipe right into absurdity. LeeLee Brazeal's "On Line Dating – Gingerman II " is what happens when Hieronymus Bosch takes a Buzzfeed quiz at 3am and starts crying about his exes. And it is glorious.

Let’s talk structure. There is none. That’s the point. This is visual chaos theory in gingerbread form. You get a page that’s all frosting and pain, cutouts of romantic caricatures bleeding literal and emotional goo. A Jason-faced cookie stares you down like your worst date from Hinge. The words are scrawled like graffiti in a junior high bathroom stall but the stall is in a motel 6 during a breakdown. There’s no safe space here. There’s no visual center. It’s all center. It’s an emotional centerfold of bad decisions and romantic dread.

And the text dear god, the text is a full-blown poetic panic attack. “I’ve had a picker,” “Not the man he used to be,” “Must have all teeth” this is brutal honesty weaponized. It’s not trying to be clever, and that makes it even more clever. Like Jenny Holzer on Tinder.

Kandy Porn is My Favorite Day of the Year

It’s Halloween’s cheap lingerie, glossy, triangular, and slightly indecent in its proportions. The yellow base is all thighs, the orange middle pure torso, and the white tip a flirtation with purity that doesn’t last long. Around it, the wall of text reads like a half-drunk confession booth: costumes that are too small, polyester capes that trap heat and smell of other people’s armpits, the humiliation of adult bodies crammed into child sized fantasies. This isn’t candy, it’s a sly dare-proof that sweetness is always threaded with something filthy, and that the real thrill of Halloween is the permission to be someone else, someone wilder, someone who doesn’t apologize for squeezing into his wrong size. You can taste the sugar, but you can also taste the sweat.

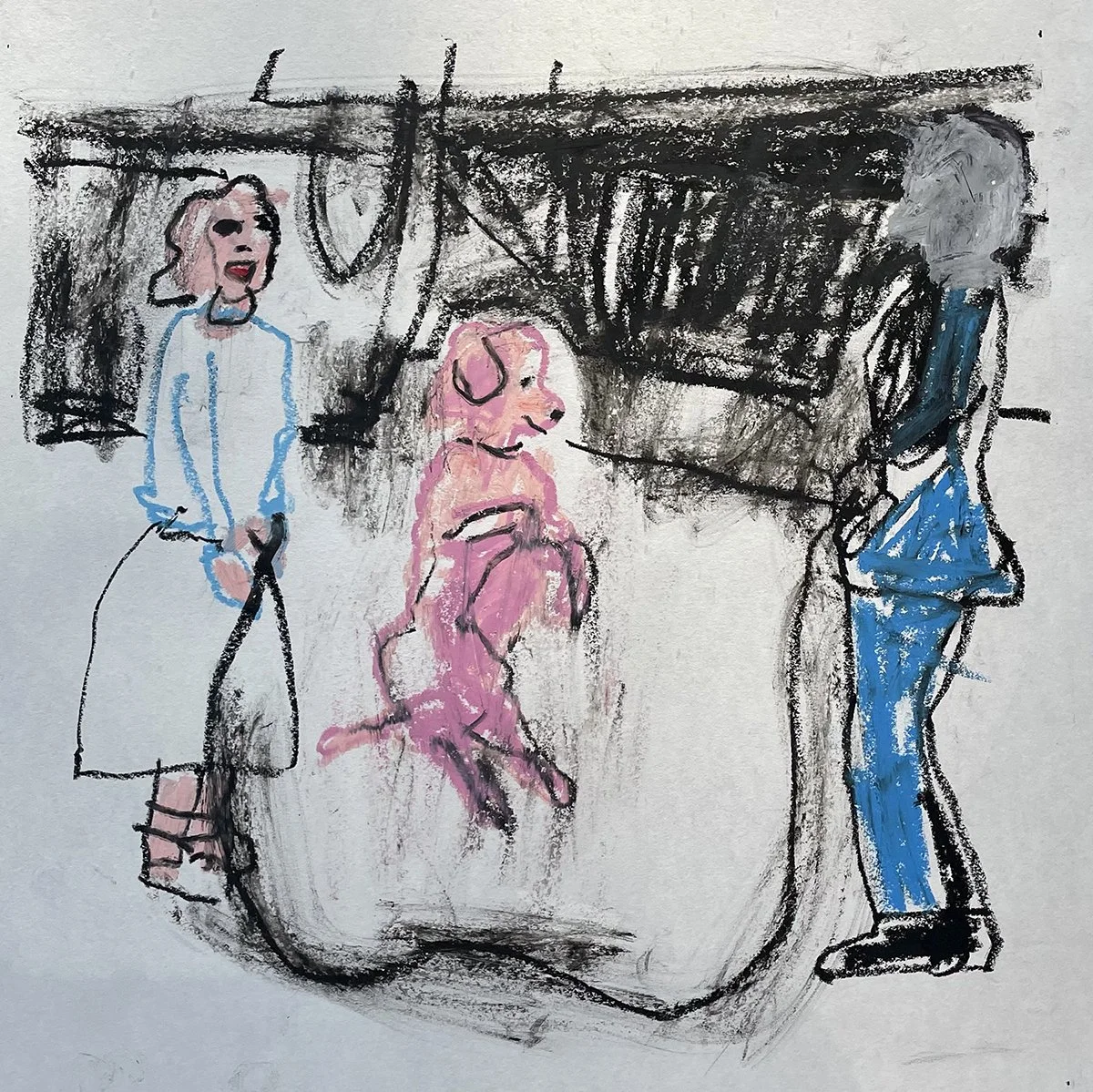

The pink poodle doesn’t just skip rope it leaps over the boundaries of species, decorum, and reason. On one side, a woman in pale blue, watchful and slightly amused. On the other, a man in jeans with his hands in his pockets, looking as if he might be here against his better judgment. Between them, the poodle is mid-air, a blur of pink and defiance. The backdrop is sketched in like an after thought, because in this strange little universe, nothing beyond this jump matters. It’s pure performance, halfway between a circus trick and a private joke.

Pink Poodle jumping Rope

Panda on Horse

The panda rides the playground horse with the grace of someone who has absolutely nothing to prove. It is not just perched, it is committed, clinging to that spring mounted absurdity like it is the last real ride in town. The friend beside it, a scribble of lines, is half imaginary, half companion, like a child’s invisible buddy finally given a body. Together, they turn the playground into a theater of the ridiculous. The horse wobbles, the panda holds on, the scribble laughs. This is childhood’s weird alchemy, how you can make friendship out of cardboard, chalk, or in this case, a wobbly ride on horse and a heap of black and white fur. It is silly, it is tragic, it is everything you remember and everything you have lost. The panda is you, the friend is everyone you cannot explain, and the horse is just the universe, bouncing under your weight.

Blue Head

This painting lives in the gap between portrait and still life. At first glance, it could be a vase stuffed with impossible blue blossoms, a bouquet so heavy it is about to topple its own container. Look again, and it is unmistakably a head—shoulders, ears, a body struggling to support the weight of what is growing on top .The cobalt mass becomes both hair and hydrangea, thought and petal. The strokes are lush and blunt, clotted together like storm clouds or tangled ideas. The vase below is flimsy, gray, almost apologetic compared to the unruly vitality above it. If it is a pot of flowers, it is one on the verge of bursting apart. If it is a head, it is one where the mind has grown so dense, so blooming, it threatens to eclipse the body that carries it.

The power of the painting is that it refuses to settle the argument. You are always toggling between head and bouquet, container and growth, the body as vessel or the vessel as body. Either way, it is bout to overflow, too much life, too much thought, too much blue for any frame to contain.

This painting screams like a billboard after midnight a gingerbread man furious with the crumbs of love gone wrong. The text piles up like graffiti confessions scrawled on bathroom stalls and desperate diaries. It is raw hilarious and pathetic all at once a tragicomic catalogueof lovers who failed the audition. The giant cookie is both executioner and victim arms wide as if to say I warned you. This is dating not as romance but as theater of the absurd where red flags are waved so violently they become banners. It is messy funny andheartbreakingly human.

My Ordinary Life: Pumpkin

This painting is Halloween as both childhood joy and adult grievance. The orange circle glows like a cheap plastic pumpkin bucket, filled with words that spill out like candy wrappers after the thrill is gone. A ghost child figure stands center stage equal parts costume and confession, surrounded by voices scolding, mocking, remembering. The humor is sharp, but so is the melancholy: pumpkins rot too fast, grown-ups sneer, and enthusiasm curdles into disappointment. What remains is the stubborn insistence to celebrate anyway, even if the mask slips, even if the pumpkin caves in on itself. It’s not nostalgia, it’s survival, painted loud enough to drown out the shame.